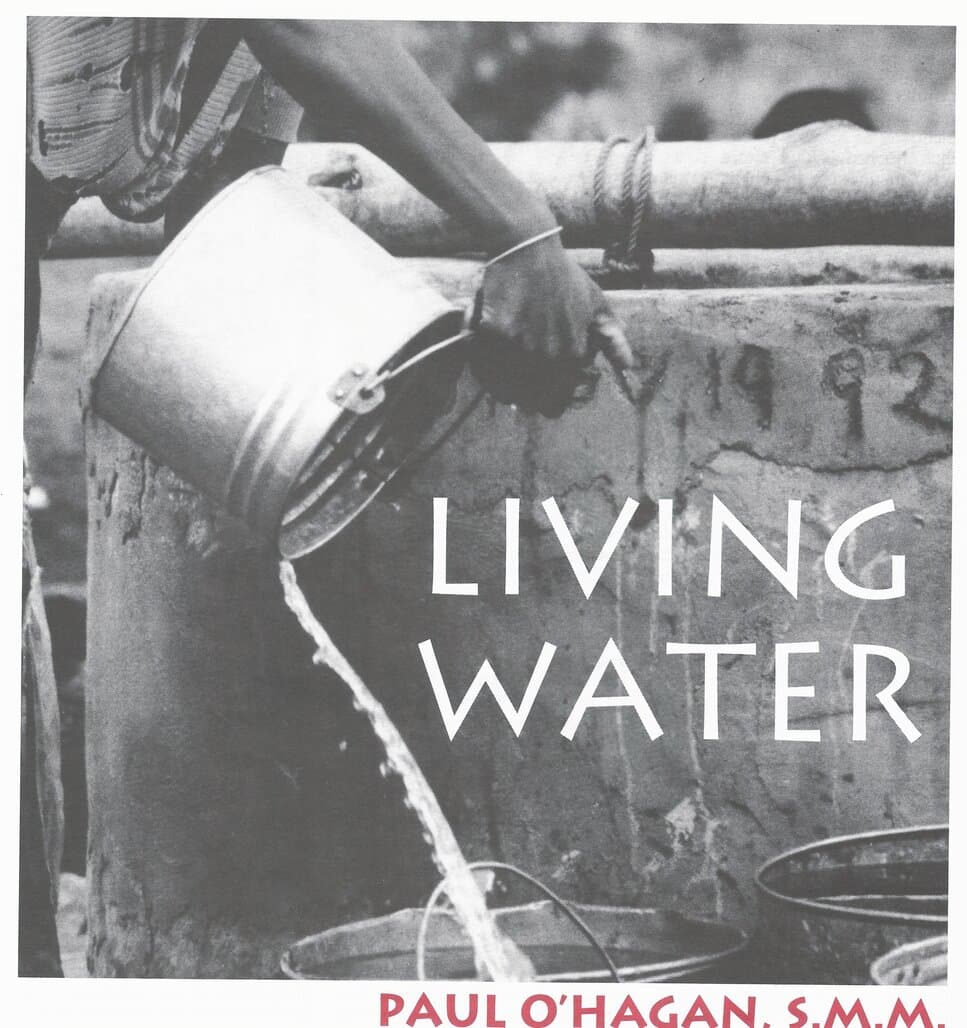

Living Waters: Montfort Missionaries in Africa

Brother Paul O’Hagan, SMM

Brother Paul is a member of Great Britain – Ireland Montfort Missionaries. At the time of this writing, stationed in Africa.

“1992 WAS THE YEAR OF CENTRAL AND SOUTHERN AFRICA’S WORST DROUCHT IN LIVING MEMORY. DURING THIS YEAR, AS A MONTFORT MISSIONARY WORKING IN THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC OF MALAWI. I WAS FACED, LIKE MANY OTHERS, WITH THE ISSUE OF WHAT COULD BE DONE. WHAT COULD BE DONE TO ALLEVIATE THE SUFFERING IN THE VILLAGES.”

Living Water

I ntrepidation and excitement grasped me, as I was held in suspension, waiting to be lowered into a 12-meter well.

A relationship of trust quickly developed. Trust as the men and women of Kasambwe village slowly lowered me into the pit beneath. This was to become a common and almost routine experience in the months ahead. A routine as I became more deeply involved in a project to save and improve the quality of life in the Chilwa Valley. Risk taking is something that one willingly does, when faced with a life-threatening situation. This project to relieve the effects of drought, was made possible only by a generous financial response to appeals.

The drought, and the added hardships it caused, was one of the contributing factors which has led to the movement for political freedom and hope for a better future in Malawi. Malawians were preparing for the forthcoming referendum on June 14th. A referendum to decide whether the country should remain under one-party rule or become a multi-party democracy. The present time has fittingly been called the Second Independence.

Wells Never Dry, Now Without Water

At the beginning of the year an alarming picture was unfolding before our eyes. Wells, which had never been known to run dry, were without water. Women and children were leaving their homes, in the early morning hours, to walk and stand in line for hours. Hours spent to draw water (often of poor quality), from the few producing wells. In anticipation of the worst months ahead, inquires were made. Inquiries as to what would and could be done by the competent authorities. The goal was to ensure safe water for the people within our area.

In the final analysis, after trudging through various church and government departments, we were left with a realization. It was up to ourselves to guarantee that something was done. At the end of the day, little was being done about the rural water problem in Zomba District. The ministry of health and water department had been crippled by the removal of development aid by the international community. This was in response to the government’s record of human rights abuses.

The bond of communal affiliation was strengthened and in some cases re-discovered by this project for the benefit of the whole community. This became powerfully evident when one village inscribed on their water source, . . One unified village through this well. A communal effort to improve and sustain the quality of life has a secondary benefit. It had unified and deepened the interdependent character of life in the village. Many villagers are surprised at what they have managed to do.

A request has arisen from some villages, to have a . . . liturgy at their well.

Return to The Queen: Articles

Hand Dug Wells

Amongst the conflicting opinions and material we could glean from the experts, we opted for hand-dug wells. This requires, however, maximum community participation and mobilization. It was the only financial option open to us on the large scale that we needed to work. With the help of an enthusiastic and committed assistant from the bankrupt ministry of health, I was turned into a well supervisor, virtually overnight! Not content to pass instructions from above, we entered into a very personal relationship with many villages. We did so by working alongside the people as the “cocooning” process of the birth of thirty-eight wells began. In a period of seven months, 51 villages were contacted, 54 well sites approved, 38 wells in 27 villages were dug, successfully found water and protected.

W hen we initiated the project we had little idea of what we were expecting ourselves or the villagers to do.

The past few months of my life have been spent underground! Actually inside the earth; inside the womb. As the womb is a place where life is nurtured, so too can “mother earth”, the world below ground, be a place of such fruit-fulness. At a time when the situation reached its worst and water was being delivered in carriers to Zomba town, by some stroke of luck we were hitting water in each and every site we chose! The digging and finding of water occurred when it was most needed and the wells were put into immediate use as soon as water was found. The accomplishment speaks for itself.

The Birth of Wells

For so many of us, unfamiliar with this experience of searching for the wellspring, it was with great excitement and anticipation that the final stages of the digging took place. As the soil became sandy, the walls began to show signs of dampness and the first trickles of water began to emerge, the whole community would gather in hope. It was amazing how the right recipe of encouragement and motivation could awaken such creativity and determination, in hungry people. As one chief commented after the completion of the village’s 12-meter well, “Our children and grandchildren will always remember that we did this work with hunger in our bellies!”

As one enters a deep well upon a line, they are frightfully dependent upon the strength in the hands of ones’ fellow toilers. The relationship between surface-to-ground drastically changes. Light becomes darkness. For the adventurous it can be a feeling of exhilaration, similar as I imagine to that of the cliff-face mountaineer; to the claustrophobic, a terrible nightmare. The work was achieved at a risk and cost that was necessary to be taken. When asked what were the villagers’ thoughts during the process of digging, I was told, “We were desperate for water and our only thought was, we must find it”. Fortunately there was only one minor injury during the whole enterprise.

T he well, along with the experience of drought, has from time im-memorial been an archetypal symbol of the human encounter with God. Living water becomes a vehicle of God’s liberation and human initiation to mission.

Wells: A Focal Point . . .

In our day, this image is being revived in some contemporary literature: Gustavo Gutierrez’ We drink from our own Wells, Thomas Green’s When the Well Runs Dry, and Anthony de Mello’s Wellsprings. Never before has this symbol had such a striking impact upon me. Through being concretely involved in the search for water, a whole wealth of symbolism has come to consciousness. As Brian Keenan, during his Lebanese imprisonment, was struck by the beauty of an orange, given by his captors after many months in captivity, so too this project has been an experience of wonder, perceived through human struggle and labor. Water equates with life. It is the thing of beauty which we have been trying so hard to find and capture.

The communal well is a focal point of the village’s life. It is an expression of community, a place where people, especially women, gather. The well is a site where people talk, exchange news and information about the latest happenings in the vicinity. At such a place of social interchange and communication, it was interesting to note that at one well, upon the freshly laid cement, a woman inscribed the Chewa proverb; Wamitseche Salipidwa, meaning, Gossiping doesn’t pay!

. . . For Community Life

The well is also a place of welcome, where travelers and passers-by stop to refresh thirsty palates. In a situation of drought, it is a lifeline upon which many people are painfully dependent. When the well does run dry, real suffering and even death is a fearful possibility. It is a symbol of how fragile life can be.

The bond of communal affiliation was strengthened and in some cases re-discovered by this project for the benefit of the whole community. This became powerfully evident when one village inscribed on their water source, Umodizi—Mkumba—Chitsime, translating as; One unified village through this well. A communal effort to improve and sustain the quality of life has a secondary benefit. It had unified and deepened the interdependent character of life in the village. Many villagers are surprised at what they have managed to do.

An Achievement of Grace

During this work many avenues began to appear. It was an endeavor which has had great significance for the district of Zomba. Never before have so many wells been dug in such a short period of time in the area. At a time when Malawi, like many neighboring counties, is suffering from an epidemic of cholera and dysentery, well protection is a necessary work which must continue. The village well improves the quality of and saves lives. The wells also results in change for women, who often walk far to draw water.

In this case, sustainable community development brought together hundreds of people from differing religious denominations and traditions, at a time of political turmoil, to work together for the common good. It developed communal skills for the benefit of a region. A request has arisen from some villages, to have an ecumenical liturgy at their well. This is an appropriate occasion to sum up and give thanks for the work that has been done, which has been an achievement of grace. Above all, these thirty-eight wells are gifts, which sustain the sacrament of life.